|

|

|

|

Mosses in Your

Wildflower Garden

by Robert Muma from Wildflower magazine,

Summer 1986 issue (Vol. 2, No. 3)

|

|

|

|

In coastal areas where there is constant humidity from fog, mist or rain,

mosses can become pernicious weeds that must be kept under rigid

surveillance and controlled with commercial moss killers. But this garden

nightmare of the coast is the stuff of dreams for those of us who live in

drier climates and want to grow mosses. We see mosses thriving in their

woodland habitats and covet them for our own backyard enjoyment. We

carefully collect some, plant them and lavish them with tender loving care -

and then probably watch helplessly as they slowly die. Mosses are

extremely selective about their environment and are growing where you found

them because all the circumstances were exactly right for them in that time

and place. Moving them to another situation, no matter how seemingly

identical, may jeopardize their welfare by lack of some quite obscure

factor(s). |

|

|

|

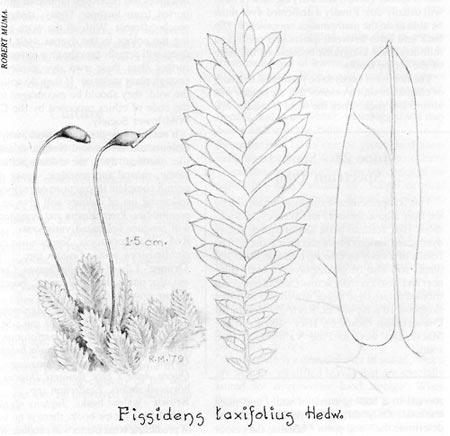

Fissidens taxifololius: A

common moss found on north facing slopes and along stream banks. It

has an extensive rhizoid system which makes it useful in preventing

erosion and forming clods of earth for easy transplanting. |

|

|

|

|

Next to lichens, mosses are probably the most environmentally sensitive group

of living things, and many species no longer grow within our urban or

industrial atmosphere. Thus it may be that it is not possible to

successfully transplant mosses which are not already native to that

locality. Some years ago I carefully planned and built a "natural" rock

garden with a pool and circulation pump and surrounding shrubbery as a

wildflower garden. Then about ten years ago when I became interested in

mosses, I thought I had what would be an ideal moss garden as well. So I

began planting samples of my collections as I brought them in. Throughout

the summer I maintained 35 species in healthy condition. Only a third of

these survived into the following spring however. And in 3 years scarcely

half a dozen of them were still living. These half dozen were species quite

common in the surrounding neighborhood anyway. Thus the cardinal rule for

growing mosses (as with all wild plants) is to duplicate as nearly as

possible, each species original habitat.

Transplanting mosses is quite a different matter from transplanting

fibro-vascular plants. For the latter, we simply dig a hole, insert the root

system and fill in firmly with earth. Mosses however have no root system to

plant in the soil. They only have short hairy fibres known as rhizoids which

serve as an anchoring system on whatever substratum is its natural habitat.

Thus when you collect moss for transplanting you have only a thin sod held

together by this network of filaments, and nothing to anchor it in place

until it becomes weathered and wedded to the soil in its new location. Every

gardener knows how notoriously curious squirrels are about anything newly

planted, and loose moss becomes a convenient toy for them. Skunks and

raccoons also, normally turn over every bit of moss they encounter for slugs

or other life that may be underneath. Even small birds will soon scratch a

loose patch of moss to bits. I found I had to make little cages of wire

netting to place over newly planted moss until it had become a firm part of

the new ecosystem. Another important precaution to this end is to pin the

moss down using pieces of wire hooked at one end to hold the moss in place.

In places where mosses may become a threat to a healthy lawn, owners

often resort to fertilizer to stimulate a more vigorous growth of grass,

believing this may then crowd out the moss. On the contrary , just the

opposite is apt to occur. Mosses need and thrive on phosphates, and soon

take over completely. The Japanese have long been famous for their moss

gardens covering large areas with a thick coat of moss of various species. I

have conflicting word-of-mouth reports only, of how it is possible to create

and maintain gardens like this, but anyone wishing to emulate their success

might consider a phosphates-rich environment as a necessary part of success. |

|

|

|

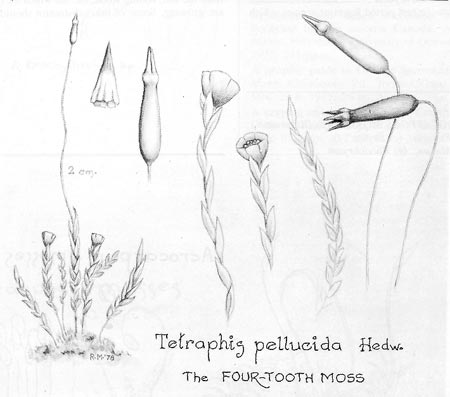

Tetraphis pellucida: A very

common cushion moss covering old rotten logs and stumps in deep,

shady, moist woods. |

|

|

|

|

Equally important for successful moss culture are almost constant shade and

plenty of moisture. Water them every day if possible. Mosses have no roots

to take nourishment from the soil directly. They get their total nutrient

requirements from the air and from minerals washed by rain from foliage

overhead. Tap water with its chlorine content may mean a slow death for

them. Tap water is also usually "hard" with a considerable calcium content.

Some mosses known as calciphiles, grow in fens or filter the calcium from

shallow mountain streams, building a cocoon of it from which they continue

to emerge endlessly. After centuries, rock formed in this way becomes many

meters deep. Non-calciphiles, on the other hand, after a summer of constant

sprinkling with tap water, may develop a whitish deposit of calcium and

gradually die. Rain water is best if it can be collected and saved for that

purpose. Or let tap water sit in a sprinkling can for a few hours to

dissipate the chlorine at least, before using. In any case, sprinkle through

overhead foliage for greater nutritional value. The growing season for

mosses begins with the melting snow in spring and continues as long as there

is adequate rain and the nights are cool. The heat and dryness of mid-summer

constitutes a hiatus or rest period for most species which may appear to be

dying. They revive quickly however with the return of rain and cool nights

of early fall and thrive hardily until covered by snow for the winter.

Spring and fall then, are the most appropriate times for collecting and

transplanting mosses. |

|

|

|

|

|

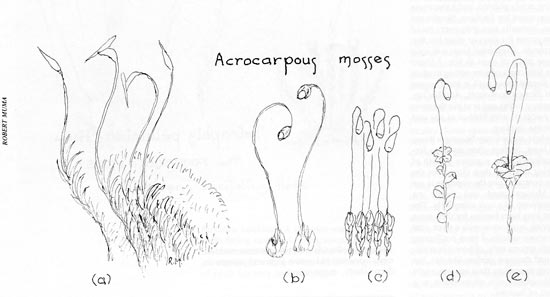

ACROCARPOUS MOSSES: (a) Dicranum

(b) Funaria (c) Bryum (d) Mnium (e)

Rhodobryum |

|

|

|

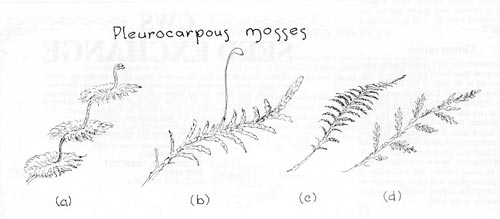

There are more than 450 different taxa of mosses found in Ontario representing

150 genera in 45 families. All of these can be sorted into just two easily

recognized growth forms. These are (I) Acrocarpous mosses which are

upright plants growing separately, or crowded together to form turfs or

cushions, and (2) Pleurocarpous mosses which are creeping plants,

lying flat on the substrata and forming mats. (See the author's

A GRAPHIC GUIDE TO ONTARIO MOSSES

on this website). |

|

|

|

|

|

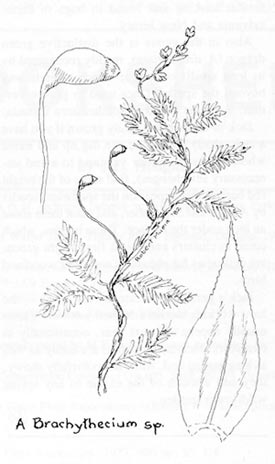

PLEUROCARPOUS MOSSES: (a) Hylocomium (b)

Pleurozium (c) Thuidium (d) Brachythecium |

|

|

|

All mosses are hygroscopic and able to store moisture in their stems and

leaves. Acrocarpous mosses, because of their gregarious nature, form

turfs or sponge-like cushions which increase their water storage capacity

and give them an advantage for survival in periods of drought. Thus the

species of this group should have a better chance of surviving transplant

than plants which have only their individual storage potential.

Pleurocarpous mosses absorb moisture from the soil, rotting wood, etc.

on which they are growing. Some of this substratum should be an essential

part of the transplant and the mosses should be covered loosely with leaves

afterward to help prevent drying. Following is a list of common genera for

each of these two groups which have representative species in almost all

parts of eastern North America: |

|

|

| ACROCARPOUS

Barbula

Bryum

Ceratodon

Dicranum

Fissidens

Mnium

Tetraphi |

PLEUROCARPOUS Amblystegium

Brachythecium

Campylium

Hypnum

Hylocomium

Thuidium

Pleurozium |

|

|

|

|

A Brachythecium species:

Brachythecium means "short capsule" which is characteristic

of the many species in this genus which is also pleurocarpous. |

|

|

|

FINAL GUIDELINES FOR MOSS CULTURE:

- Plenty of shade and moisture is the first essential.

- make your garden as natural as possible. Ideally, it should contain a

variety of soils as well as rotting wood, and a few rocks such as limestone

and granite in separate areas.

- Rocks, a board fence, or protective growth of some kind are necessary to

shield them from drying winds.

- Most important is the nature of the substratum from which the moss was

collected: the soil and its pH factor; living or rotting wood; rock, acid,

or alkaline. Transplant some of this substratum to blend into its new

habitat.

- Some mosses grow mainly in the shelter of one species of tree; others of

another species. Still others favour the proximity of certain metal-bearing

rocks. Putting your mosses in the wrong context may only provide them with a

hasty demise.

|

RECOMMENDED READING:

- Bryophytes, tiny treasures of the plant world. P.K. Armstrong.

The Morton Arboretum Quarterly 17(2):17-30. 1981

- Mastering the moss garden. J.L. Creech. The Mother Earth

News. Special series #9. Spring. 1984.

- Mosses of Eastern North America. H. Crum & L. Anderson. Columbia

University Press. New York. (2 vol.). 1981

- Mosses in landscape gardening. A.J. Grout. The Bryologist

34(5):64. 1931

- Gardens: cloaked in moss. T. Heineken. Architectural

Digest. Oct 1984. pp 162-166.

- Checklist of the mosses of Ontario. R.R. Ireland & R.F. Cain.

Pub. in Botany #5. National Museums of Canada. Ottawa. 1975. 67pp.

- Checklist of the mosses of Canada. R.R. Ireland et al.

National Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa. 1980. 75pp.

- Mosses in Japanese gardens. Z. Iwatsuki & T. Kodama.

Economic Botany 15:264-269. 1961

- Bryophyte and lichen succession on decaying logs in eastern Canada.

H. Muhle. PhD thesis. University of Ottawa. 1973. 241 pp.

- A graphic guide to Ontario mosses.

R. Muma. Toronto, Ontario. 1985. 28pp. (CLICK

HERE)

- A cryptogamic flora of Elgin County, Ontario. Part I. W.G.

Stewart. Ontario Field Biologist. 30(2):17-41.

|

|

|

|

Robert Muma is a biological

illustrator. bookbinder, leather craftsman, writer, gardener and

photographer. He lives in Toronto, Ontario where he has a personal herbarium

of over 2000 moss specimens from around the world. |

|